First things first: How did the Epiphone Jack Casady Signature Bass come about?

Well, I ran into the Gibson version of this bass while I lived in New York in around 1986. In the late '60s, I had played the Guild Starfire bass, and done a lot of electronic work on it with the folks that ended up becoming Alembic -- Owsley Stanley and Ron Wickersham and Rick Turner. I had worked with those semi-hollowbody basses and enhanced them, but they were short-scale necks. Eventually, I stopped playing those basses and went back to a full 34-inch scale neck, but I wasn't able to find F-hole basses with a full scale. When I saw the Gibson Les Paul [bass], it was something that had slipped under the radar for me. I hadn't seen it before. It apparently was produced in a small batch in the early '70s, and I played it and really loved it. It had that full scale, which meant the low end, the low E string, was nice and full and rich. But because of the semi-hollow body, it had a really nice sweet top end.

So I bought it and played it for a few years. But I always thought that the pickups were somewhat deficient, particularly in a modern band where you have so much competition on the low-end -- particularly if you play with any keyboard instruments. I noticed the sound was sort of getting lost when you played with a full band. So I approached Michael Lawson, who was working for Gibson at the time, to see if they would reissue it or if I could get involved in the redevelopment of that kind of style bass. At Gibson -- although they weren't interested, because it's such an odd duck -- Mike walked over to the Epiphone division, which Gibson owns, to Jim Rosenberg, and put forth my proposal to get a semi-hollowbody full-scale neck up and running in their line.

And Epiphone was receptive to the idea?

Jim was very enthusiastic about it, and backed me up completely. He went beyond anything I ever thought would happen with the president of a guitar company, and we started the research. We started making the early test models of the instruments that were made then in Korea, and I was really impressed with the workmanship that was coming back out. The other issue that I wanted to address and develop was the pickup. I spent a couple weeks in Nashville with J.T. Riboloff, who was the main electronics man for Gibson. I went down to Nashville and booked a hotel room and went in every morning at 9:00, and we worked on these pickups. We tried different windings and different combinations.

What were your goals in redesigning the pickup?

What I wanted was a good, thick sound that was sort of patterned after those nice old '30s and '40s lap-steel guitars, where they used nice fat wire around the alnico magnets...One of the reasons I wanted to do that was to boost the output somewhat, because it's a low-impedance setup on the bass. The philosophy behind low-impedance, Les Paul himself really believed in. His instruments were low-impedance...the idea was that you got a more high-fidelity, full-dynamic-range sound. You didn't get as much power as far as output, but the tone was just amazing. I wanted to keep that full range. So we worked on that; getting it to sound pretty good.

It took over a year to develop the bass and the pickup after I got home from that Nashville session. And then we worked on the manufacturing process to make sure the instrument would actually come out on the street with the proper sound. I think it took about 14 months, and they were getting a little antsy, you know, wondering when I was going to finally give the okay -- because I think I had about nine or ten different mock-ups; different combinations of approaches. But it finally all worked out. It worked out wonderfully. This was all 1998. And to my amazement, it's still out there all these years later -- almost 15 years later -- and sounds better than ever.

Epiphone Jack Casady Signature Bass

Have you had a chance to check out the new Silverburst limited edition?

As a matter of fact, Jim just sent me two of them...Every time there's a new production line, I bring out two new basses, and that's what you see me playing out there. I keep track of the production value and make sure those instruments are up to snuff, so I can pick one up right out of the store and set it up to my liking, and have it sound really good.

Would you say that you prefer the new Epiphones you play on tour and in recording to the original vintage Gibson?

Oh, absolutely. I've got three of the originals. You know, it's always great to have vintage instruments…but just because it's a vintage instrument doesn't necessarily mean it's going to sound better.And one of the things I thought was lacking was the pickup, and I brought the pickup up to standard. My goal was to make sure that for engineers in studios, this was an excellent recording bass. That's one reason I used one pickup and one pickup only. I remember Jim saying, "Jack, I'll give you anything -- you want three pickups, you can have three pickups." I said, "You know, Jim, what I want is one really top-notch, no-holds-barred quality pickup that is properly centered in the speaking length of the string to get the full harmonic range. Then a musician should let his hands do the rest of the work." I wanted an instrument that responds to the various dynamic approaches of different players -- and dynamic approaches that use up the speaking length of the string with your right and left hand. That's what you manipulate in order to get different tones out of the instrument -- and if the instrument will respond to that, then I think you have one instrument that will do a lot for you.

Epiphone Jack Casady Signature Bass

On the Epiphone, you also have the three-position tone switch. What options does that add?

That's an impedance switch, and what that does is kind of close down the dynamic range. I personally keep it in the first position, which is 50 ohms. That gives me a complete tone -- a really wide dynamic range. It's pretty funny: it doesn't come off as loud as other instruments, meaning the hotness of the pickups -- but then again, that's why you have an amplifier. I got involved in the '60s with putting active electronics in basses for a while…I found that after extensive playing, I was getting a little bit too much of the preamp sound that I couldn't change with my hands. I was committed to a sound. I find that with passive instruments, you really get the instrument sound you can manipulate with your hands. That's how it is with the Jack Casady Signature Bass.

I've been playing the instrument for 15 years, and it's my favorite. That's the one I pick up at home. I've got other instruments for special occasions and certain situations where other instruments fit the bill. But the kind of playing I do -- both with electric Hot Tuna and acoustic Hot Tuna -- I can move between the electric world and acoustic world. In the acoustic world I can get a beautiful tone that won't blow out the acoustic guitar that Jorma Kaukonen plays. He plays in a fingerstyle: Piedmont style, with thumb and two fingers. He's not thrashing on that acoustic instrument; it's a very light touch. So they complement each other well, the two instruments. But if I want to get up with a full band, like we're going to do for the first third of the upcoming Hot Tuna tour -- that you can read all about on hottuna.com or JackCasady.com -- shameless plug -- then I can get plenty of gank and growl and a good fat solid sound, particularly a good, clear, distinct low-end sound that you can separate from the rest of the band.

It seems like the semi-hollowbody is the ideal style for you since it can cover so much territory, as you have with Hot Tuna and other projects.

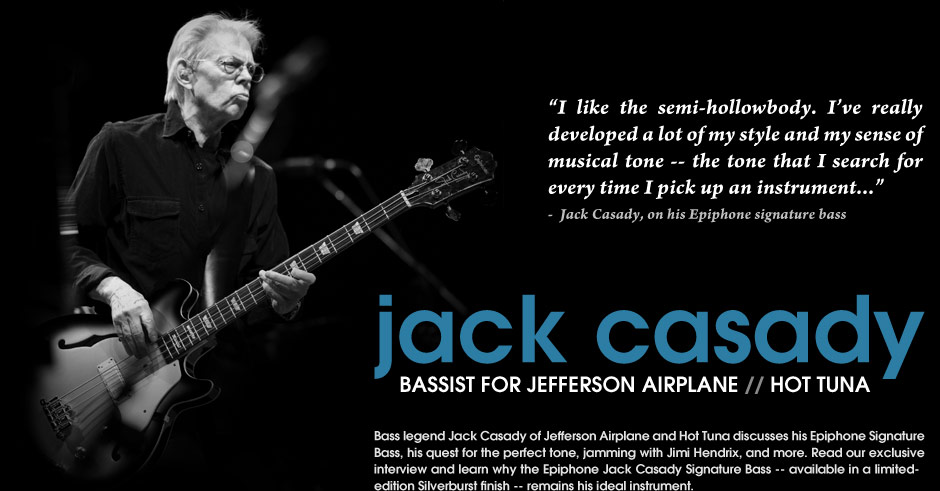

I think, sooner or later, you marry yourself to an instrument. I'm not wild about changing instruments all the time. There are players that love to be playing whatever the latest thing that's out all the time. I like the semi-hollowbody. I've really developed a lot of my style and my sense of musical tone -- the tone that I search for every time I pick up an instrument. I'm a little more satisfied with the semi-hollowbody approach.

You mentioned Jorma playing the fingerstyle. Listening to Hot Tuna records, the way his thumb works really adds a lot of rhythm to the music. How do you think your bass playing has responded to his style?

Well, that's the essential component that's allowed me to develop a more melodic, and at times more chordal, style on the bass. When we first started messing around in hotel rooms in the mid-'60s, I had this little rig that I built out of a Halliburton flight case, a pilot's flight case. One of my equipment guys had put together a speaker and miniature amplifier in there, and I used to carry that everywhere. [Jorma would] be playing his Gibson J-50...In that dynamic, in small rooms working out material -- beginning with Reverend Gary Davis material and Blind Blake, stuff like that, that uses that style of fingerpicking guitar -- by him keeping the pulse and alternating lower strings, sometimes in octaves, sometimes in fifths, that would give that bass back-and-forth feeling to the music. That released me from just being on the low-end, doing those essential foundation works. So when I wanted to do a line that went into a higher register, the bottom didn't fall out of the song.

When you first started off, you were playing mostly guitar. Do you think that also influenced the melodic style you're known for?

Well, yes. I started out playing guitar at age 12, and when Jorma and I had our first band together in the late '50s. I think you're absolutely right: I have a sense of melody and awareness through the guitar. But at the same time, I was always a fan of orchestral work and classical music, and being in Washington, D.C., I had a wonderful opportunity to hear so much music. I was always fascinated with the orchestras, where they take that low end and have maybe eight double basses playing at once, and then they move it into the cello range; they move the melody of the piece through the orchestra. I was always used to hearing the low end move more melodically, and it makes perfect sense to me. So I think that required a format, and I wasn't really able to approach that format, I think, until I joined the Jefferson Airplane at Jorma Kaukonen's request, after he joined in 1965. I came along three months later, and I found a situation where there was a lot more freedom in the thinking of arrangement of the music -- where sometimes the music was so loose, it was definitely anathema to New York arrangers or Los Angeles arrangers. But for me, at that particular time, being around 21 years old, it was the perfect time for me to free myself from other preconceptions in the bass-playing world, and to move in another direction -- sometimes with success, and sometimes with not so much success, but that's the nature of it.

In addition to Jefferson Airplane and Hot Tuna, you've played with a lot of legendary artists, like David Crosby, Warren Zevon, and even Jimi Hendrix. Can you tell us about the Hendrix experience?

Funny choice of words. It was great. Jimi was a very gentle and a very nice guy. I got to be friends with him, and also good friends with Mitch Mitchell, his drummer at the time. When he left the United States and went to England and put his wonderful band together, it allowed him to do the very thing I was talking about earlier: it gave him a format to break away from the kind of stuff he was playing as a journeyman coming up through the ranks.

Bill Graham was our manager for a period of time in around '67, and when Jimi Hendrix and the band would come through San Francisco and play the Fillmore, we had a rehearsal facility next door. I was able to hang out and jam a bit at every opportunity. Back in those days, musicians loved to meet other musicians and check each other out. To make a long story short, when he was doing his Electric Ladyland project in New York City, the Jefferson Airplane was there. We were doing a TV show -- Dick Cavett, I think -- and we taped that, and afterwards, we went to see Traffic on their debut tour of the United States. Jimi had known Steve Winwood from England, and we met up there at a club called Steve Paul's Scene, and he invited a whole bunch of us -- about 20 from the two bands -- back to his studio to watch him record.

About 7:30 in the morning, after being up all night long, he said, "Let's do a blues." I said fine, and Mitch Mitchell and Jimi and I laid those tracks -- a fifteen-minute track, which was unheard of then. No one expected it to go on an album. We did "Voodoo Chile." About a month later, he gave me a call and said "Do you mind if I put this on the album? We're going to expand it to a double album." I said, "Of course not." And it became a piece of history. It was great fun to do. We played five or six times together at Winterland and Oakland Coliseum, and so there I had a hook, a song I worked on with him, and he'd invite me on stage very kindly. And Noel Redding would go to second guitar, and I'd play bass, and we'd have a ton of fun.

You recorded the new Hot Tuna album, Steady As She Goes, in Levon Helm's studio...

Yes, the late Levon Helm, who was such a good friend to us, and such a warm human being. And he made a wonderful studio out there...I was able to get a huge rock 'n roll sound, and a very delicate sound for the acoustic stuff.

Any other projects on the Jack Casady radar that we should know about?

Well, we're going to be touring a lot. Immediately ahead, we're hunkering down and promoting this album, and I do a lot of teaching at Jorma Kaukonen's Fur Peace Ranch guitar camp as well. So that keeps us pretty fully booked. In December, we'll be in New York for two nights at the Beacon. And next March, we go to Jamaica.